Kvadrat is a 2013 documentary feature film written, co-produced, and directed by Anatoly Ivanov. The film explores the realities of techno DJing, using the example of Russian DJ Andrey Pushkarev. Filmed as a hybrid between a road-movie and a music video, Kvadrat not only illustrates the festive atmosphere of techno night clubs, but also reveals the lesser known side of this profession. Shot in Switzerland, France, Hungary, Romania and Russia, the film omits the typical documentary elements: no interviews, no explanatory voice-over, no facts, no figures. It gives priority to abundantly sounding techno music, leaving the detailed interpretation to the viewer.

Cinematically, Kvadrat is of note for its distinctive color photography, intricate sound design, attention to details and lack of traditional dramatic structure, achieved on a very low budget.

Thinking out loud...

Forum rules

By using this "Production" sub-forum, you acknowledge that you have read, understood and agreed with our terms of use for this site. Click HERE to read them. If you do not agree to our terms of use, you must exit this site immediately. We do not accept any responsibility for the content, submissions, information or links contained herein. Users posting content here, do so completely at their own risk.

Quick Link to Feedback Forum

By using this "Production" sub-forum, you acknowledge that you have read, understood and agreed with our terms of use for this site. Click HERE to read them. If you do not agree to our terms of use, you must exit this site immediately. We do not accept any responsibility for the content, submissions, information or links contained herein. Users posting content here, do so completely at their own risk.

Quick Link to Feedback Forum

Re: Thinking out loud...

Re: Thinking out loud...

Saw him play in Lodz, boring tech house/dub techno DJ

SoundcloudSoiree wrote:Ima invert a photo of my self inverting a photo of myself.

EBM, Kwaito, Japan, Lutto Lento

Re: Thinking out loud...

In The Studio: Break

Break is one of the most revered names in drum & bass, famed for the quality and consistency of his music over the past 15 years. Now the Symmetry Recordings boss is giving other producers the chance to add a bit of Break magic to their tracks by releasing his first ever sample pack, Symmetry Drum & Bass. We spoke to the man himself to find out more about it and how he works in the studio.

At what age did you get into producing and how did you learn?

I got some decks when I was 15, and started with Cubasis and a couple of sound modules. When I got an Emu sampler the manual that came with it taught me a lot, each section explained Compression, EQ, Drive, etc. really simply which you don't often get these days.

When I started working with Silent Witness he showed me Logic 5 and taught me how to use it. I preferred it to Cubase so switched over and felt more creative.

A lot of it was trial and error and teaching yourself a lot, there were no internet tutorials back then.

How did you get your music noticed in the beginning?

My lucky break was when MC Zoobee heard a bootleg remix of Planet Dust I was playing off a minidisc at a record stall in Camden market.

He knew DJ A-Sides and thought my tracks would be up his street. I went up to see A-Sides and he released my first few tracks on Eastside Records and hooked me up with some good people in the scene. I'm eternally grateful.

How do approach starting a new tune? Do you have a standard workflow of building beats/bass first, or focus on another part to begin with?

It's about fifty fifty, if I'm making a musical tune I usually get the melodic elements in first, get the chord structure and leave the bassline till later.

With the more tech/ dancefloor tunes, the drums usually are first - getting the right groove is really important, that will also often influence the groove and pattern of the bassline.

Does your approach differ depending on which genre you are making?

Sort of answered it above, but if it’s a vocal tune when mixing I'll try and make that the focus of the mix. With a lot of tracks in dnb the vocal is lost in the background, which I find really annoying.

When making house or pop stuff I often listen through small cheap computer speakers to get the main elements correctly balanced without being able to hear much bass.

Sub isn't as that important in those genres, so I try and make the mix sound full on small speakers with the vocal and kick being the focus more.

How do you come up with melodies or chord progressions?

I just sit at the piano and play stuff really. If it’s a vocal track or remix I mainly try and find a progression that works around the lead melody that harmonises and complements the vocalist. That’s probably my favourite part of making a track, it’s actually writing music than just engineering, which often ends up as 90% of the job.

Out of the tracks you do start, how many get finished? How many get released?

Probably about 50-60% of dnb tracks get released. It kind of changes depending on the year. Recently I've been trying to get that percentage up by starting tunes less half arsed and committing to dead certs more.

Where is your studio set up and what does is consist of? Do you use any hardware or are you software only?

My studio at the moment is in Motion Club in Bristol. We had some custom rooms built last year, so it’s been great to finally get into a professional space and give the ears some certainty.

I do use some hardware but mainly for vocal and instrument recordings such as 1176 Compressor and Api Pre-amps. I still love my Dbx compressors but mainly it's software for production these days.

The UAD plugs really enabled me to switch over from analogue to digital mixing because they do sound realistic, and the real outboard is all way out of my price range.

What are the best tools for beginners?

I think synths with good presets and simple interfaces such as Absynth or Diva are great for beginners as you can get good sounds out of it without having to program for two hours. Most people want instant gratification.

I've got no problem using a preset if you play something good with it. The Waves One Knobs are quite crude but easy if you want it brighter or fatter etc. I thought it was a good idea for getting something into the ballpark quickly, things can always be refined later.

What are your favourite plugins and synths?

I love the UAD plugs for their real analogue sound, Softube are fantastic on the same front. I'd recommend a real synth any day over soft synths, it’s kinda the difference between cotton or nylon. I also love Airwindows and Waves plugs.

Most of it for me is finding the right plug for the job, I've got about 40 compressor plugins, which one to use is more the problem, getting about favourite plugins you know and like is probably the best bet for consistent results.

What's the coolest bit of kit you own?

My new 12” Eve sub woofer. I've waited my whole life to sit in my studio with proper heavy bass, always had neighbours etc so that gives me a smile every day.

What's the best piece of equipment you've ever used?

I've used some expensive stuff, but I always maintain that the Dbx 266 XL is the best unit for the price I've seen. I was also blessed with some Audeze headphones a while back, they are incredible.

Which sequencer do you use and why?

I still use Logic 9. It’s a total love hate relationship, but it makes sense to me. Terrible shame it’s owned by Apple now and all the original staff left to got to other companies. I never feel I have time to learn another program, after half a day I get fed up and go back to Logic. I use Protools when working with DJ Die, I think it’s great, but still don't know my way round it fully.

What audio interface do you use?

I normally use an Allen & Heath ZedR 16 Firware interface/ desk. I've had a few problems with it so have been using a small Edirol USB soundcard, which has never gone wrong, so I like that.

Any new studio technology or gear you like at the moment?

I'd love to get a high-end sound card, it just seems like such a boring spend of 2-3 grand, there's not even any knobs to twiddle.

I do like the look of the Softube Consol 1. The Harrison mix bus is great, but the routing can be an issue for me... I have no idea why Logic and Protools don't give you the option of analogue desk modelling, it’s the obvious way out of horrible digital mixer sounds.

What’s your monitoring situation like?

I use EveAudio SC208's with and Eve TS112 sub woofer. I have some Adam AX3's as an NS10 equivalent, also some Maplin £10 computer speakers. I have the Audeze LCD2 and LCD3 for headphone monitoring.

How do you go about compression, do you compress each track individually?

It all varies to be honest, usually each drum track will have individual compression but a lot of the heavy lifting is often done on the drum buss to glue the drums together.

I sometimes parallel compress elements nearer the end of the mix if more fullness is still needed, or to get a blend of compression without ruining the original signal.

Any advice you can give us regarding mixdowns and mastering?

My main gripe from doing mastering and going to many of my own mastering sessions is tambourines and hi-hats that are too loud and bright compared to the rest of the mix.

It doesn't really matter if your tune is too bright or dull, it’s more the balance of the sounds within that will result in a good finished master. You can't mix the tune down again in mastering, that's what I always try to remember.

What production technique do you think is really overused / annoying?

Has to be loud over the top build-ups that go on for two minutes and then have a really lame drop.... half of all dance music basically.

What do you know now that you wish you had known when you started out?

That after specialising for 15 years your product will get valued at about 30p on the internet. I'd probably have done a sample pack sooner.

What’s key to creating your own sound?

Using the influences you love to define your sound, then it'll be true and you might actually like your own music.

Taken from here - http://www.kmag.co.uk/editorial/musicte ... rview.html

Break is one of the most revered names in drum & bass, famed for the quality and consistency of his music over the past 15 years. Now the Symmetry Recordings boss is giving other producers the chance to add a bit of Break magic to their tracks by releasing his first ever sample pack, Symmetry Drum & Bass. We spoke to the man himself to find out more about it and how he works in the studio.

At what age did you get into producing and how did you learn?

I got some decks when I was 15, and started with Cubasis and a couple of sound modules. When I got an Emu sampler the manual that came with it taught me a lot, each section explained Compression, EQ, Drive, etc. really simply which you don't often get these days.

When I started working with Silent Witness he showed me Logic 5 and taught me how to use it. I preferred it to Cubase so switched over and felt more creative.

A lot of it was trial and error and teaching yourself a lot, there were no internet tutorials back then.

How did you get your music noticed in the beginning?

My lucky break was when MC Zoobee heard a bootleg remix of Planet Dust I was playing off a minidisc at a record stall in Camden market.

He knew DJ A-Sides and thought my tracks would be up his street. I went up to see A-Sides and he released my first few tracks on Eastside Records and hooked me up with some good people in the scene. I'm eternally grateful.

How do approach starting a new tune? Do you have a standard workflow of building beats/bass first, or focus on another part to begin with?

It's about fifty fifty, if I'm making a musical tune I usually get the melodic elements in first, get the chord structure and leave the bassline till later.

With the more tech/ dancefloor tunes, the drums usually are first - getting the right groove is really important, that will also often influence the groove and pattern of the bassline.

Does your approach differ depending on which genre you are making?

Sort of answered it above, but if it’s a vocal tune when mixing I'll try and make that the focus of the mix. With a lot of tracks in dnb the vocal is lost in the background, which I find really annoying.

When making house or pop stuff I often listen through small cheap computer speakers to get the main elements correctly balanced without being able to hear much bass.

Sub isn't as that important in those genres, so I try and make the mix sound full on small speakers with the vocal and kick being the focus more.

How do you come up with melodies or chord progressions?

I just sit at the piano and play stuff really. If it’s a vocal track or remix I mainly try and find a progression that works around the lead melody that harmonises and complements the vocalist. That’s probably my favourite part of making a track, it’s actually writing music than just engineering, which often ends up as 90% of the job.

Out of the tracks you do start, how many get finished? How many get released?

Probably about 50-60% of dnb tracks get released. It kind of changes depending on the year. Recently I've been trying to get that percentage up by starting tunes less half arsed and committing to dead certs more.

Where is your studio set up and what does is consist of? Do you use any hardware or are you software only?

My studio at the moment is in Motion Club in Bristol. We had some custom rooms built last year, so it’s been great to finally get into a professional space and give the ears some certainty.

I do use some hardware but mainly for vocal and instrument recordings such as 1176 Compressor and Api Pre-amps. I still love my Dbx compressors but mainly it's software for production these days.

The UAD plugs really enabled me to switch over from analogue to digital mixing because they do sound realistic, and the real outboard is all way out of my price range.

What are the best tools for beginners?

I think synths with good presets and simple interfaces such as Absynth or Diva are great for beginners as you can get good sounds out of it without having to program for two hours. Most people want instant gratification.

I've got no problem using a preset if you play something good with it. The Waves One Knobs are quite crude but easy if you want it brighter or fatter etc. I thought it was a good idea for getting something into the ballpark quickly, things can always be refined later.

What are your favourite plugins and synths?

I love the UAD plugs for their real analogue sound, Softube are fantastic on the same front. I'd recommend a real synth any day over soft synths, it’s kinda the difference between cotton or nylon. I also love Airwindows and Waves plugs.

Most of it for me is finding the right plug for the job, I've got about 40 compressor plugins, which one to use is more the problem, getting about favourite plugins you know and like is probably the best bet for consistent results.

What's the coolest bit of kit you own?

My new 12” Eve sub woofer. I've waited my whole life to sit in my studio with proper heavy bass, always had neighbours etc so that gives me a smile every day.

What's the best piece of equipment you've ever used?

I've used some expensive stuff, but I always maintain that the Dbx 266 XL is the best unit for the price I've seen. I was also blessed with some Audeze headphones a while back, they are incredible.

Which sequencer do you use and why?

I still use Logic 9. It’s a total love hate relationship, but it makes sense to me. Terrible shame it’s owned by Apple now and all the original staff left to got to other companies. I never feel I have time to learn another program, after half a day I get fed up and go back to Logic. I use Protools when working with DJ Die, I think it’s great, but still don't know my way round it fully.

What audio interface do you use?

I normally use an Allen & Heath ZedR 16 Firware interface/ desk. I've had a few problems with it so have been using a small Edirol USB soundcard, which has never gone wrong, so I like that.

Any new studio technology or gear you like at the moment?

I'd love to get a high-end sound card, it just seems like such a boring spend of 2-3 grand, there's not even any knobs to twiddle.

I do like the look of the Softube Consol 1. The Harrison mix bus is great, but the routing can be an issue for me... I have no idea why Logic and Protools don't give you the option of analogue desk modelling, it’s the obvious way out of horrible digital mixer sounds.

What’s your monitoring situation like?

I use EveAudio SC208's with and Eve TS112 sub woofer. I have some Adam AX3's as an NS10 equivalent, also some Maplin £10 computer speakers. I have the Audeze LCD2 and LCD3 for headphone monitoring.

How do you go about compression, do you compress each track individually?

It all varies to be honest, usually each drum track will have individual compression but a lot of the heavy lifting is often done on the drum buss to glue the drums together.

I sometimes parallel compress elements nearer the end of the mix if more fullness is still needed, or to get a blend of compression without ruining the original signal.

Any advice you can give us regarding mixdowns and mastering?

My main gripe from doing mastering and going to many of my own mastering sessions is tambourines and hi-hats that are too loud and bright compared to the rest of the mix.

It doesn't really matter if your tune is too bright or dull, it’s more the balance of the sounds within that will result in a good finished master. You can't mix the tune down again in mastering, that's what I always try to remember.

What production technique do you think is really overused / annoying?

Has to be loud over the top build-ups that go on for two minutes and then have a really lame drop.... half of all dance music basically.

What do you know now that you wish you had known when you started out?

That after specialising for 15 years your product will get valued at about 30p on the internet. I'd probably have done a sample pack sooner.

What’s key to creating your own sound?

Using the influences you love to define your sound, then it'll be true and you might actually like your own music.

Taken from here - http://www.kmag.co.uk/editorial/musicte ... rview.html

Re: Thinking out loud...

In The Studio: Matta

Bass music duo Matta have just released a sample pack called Dark Garage & Dubstep on Samplephonics. Read on to discover how they approach working in the studio and how you can win one of three packs we have to give away.

How do approach starting a new tune?

We pretty much always start with the drums in order to get a good groove and a solid foundation for the track. When we first started out producing, as soon as we had the drums working, we would always dive straight into the bassline as that has always been the most enjoyable part for us.

We found that a better approach is to build up some FX sounds, pads, drones, extra percussion - and in some cases a whole intro - to give the track a little bit more depth and a texture before attempting the bassline.

Do you usually wait till you're in the right state of mind before starting a track or do you just sit down and see what comes out?

It would be a luxury to always be in the right state of mind before starting a new track. We always try and get an idea of what we want to make before we start something new but sometimes we just jump in a see what happens.

It will often take longer to get something working but the results can sometimes be more interesting. We have banks and banks of synth presets we have made to use as a starting point too.

Does your approach differ depending on which genre you are making?

Not hugely in terms of the way we would build a track from the ground up. We'd still usually start with a beat but, in the case of a more chilled out track, we would definitely concentrate more on the overall soundscape and get some melodic elements first. In the case of a heavier track we would concentrate more on the bass and variations of it.

Out of the tracks you do start, how many get finished? How many get released?

It's difficult to say but probably around two tracks get started to every one we finish. We have quite a few unfinished tracks on our hard drive and if we are really stuck for inspiration sometimes we go back and have a look at half-finished projects as a starting point.

However, when we go back to tracks we make sure we really strip them down in order not to end up having the same problem of not being able to finish it again.

What do you do when you're not feeling inspired?

Other than going back to half-finished projects, it's mainly simple things like doing anything else, going for a walk, listening to some tracks from other artists we like or even to listen to music outside of the genre to clear the palate.

There is always things we can do like, play around with a synth and see what it is capable of, make some new sounds, organise sample libraries, etc. Days where we lack inspiration is always a good opportunity to catch up on listening to promos we get sent too. There is also Countdown and Deal Or No Deal!

Where is your studio set up and what does is consist of? Do you use any hardware or are you software only?

The studio is set up at home and it consists of a Mac desktop, Focusrite Sapphire, a pair of Behringer controllers (BCR & BCF 2000s) and a Novation Xiosynth. We work pretty much solely in the box. We often record found sounds through a mic or onto a recently purchased Zoom h4n to include in our tracks. We have a few banks of random percussion and sound effects made this way.

What's your most used plugin?

Probably sample delay. We use it a lot on our FX and percussion parts. If you delay the left or right signal by about 600 - 800ms the sound appears a lot wider which helps with bringing things out of the mix.

Another plugin we use a lot is the Tone2 filterbank. It's got some quite unusual filter types and we use it to either completely change the shape of a sound or subtly add movement to it. Also we love the Reaktor Space Master reverb because it can be used to both create space and mangle sounds.

Are you the sort that likes to use old vinyl to get snippets of atmos, FX, melodies, etc or do you use synths mainly for your sounds?

We mainly use synths and try and sculpture things from scratch to try and give it an individual sound. We have been known to get out microphones and sample various things which can be really interesting once you clean them up and apply some crazy effects to them. The only sampling we have ever done from vinyl is from old battle records where you can get some nice snippets of vocals or stabs which can sit in the background of a track and build an atmosphere.

What's the coolest bit of kit you own?

Without doubt it's the Korg Monotron. We've never used it for a bassline but it's quite fun to mess around with and record weird effects and riser sounds into the sequencer. There are other bits of slightly more sophisticated equipment we've had access to but the immediacy and simplicity of the Korg makes it the coolest.

What's the best piece of equipment you've ever used?

A friend of ours had a Novation Bass Station which was a lot of fun to mess around with. We've never used one on a track but for sheer hands-on fun you couldn't beat it.

Which sequencer do you use and why?

We use Logic and have done for some time now, but we rewire it with Ableton to use the time stretching and sampler functions. Ableton handles that stuff so much better than Logic. I actually think the way things are handled in Ableton makes the workflow very good but we still prefer the Logic environment and the standard plugins that come with it.

A lot of producers we know have made the switch to Ableton but we are so comfortable with using Logic that it's hard to justify changing when we can use the best bits of both programs using Rewire.

What’s your monitoring situation like? What speakers and / or headphones do you use?

We have a pair of Genelec 8020's with a Genelec 5040 sub. When we are on the road we just use the headphones we are most familiar with the sound of - which happen to be a pair of cheap Phillips in ear headphones - but we always do the mixdown in the studio as they are nowhere near accurate enough for detailed mixing.

Any advice you can give us regarding mixdowns?

Firstly, we always try and put a bit of time between finishing the track and mixing it down. That really helps us notice things that we may have just got used to when writing. Always low cut things to leave enough room for the sub and hi cut things to make room for things like percussion, hats and rides.

Also, we never mix with any limiters on the master. We also like bussing all our drums together to process. compress and effect as a whole and we usually do the same with bass sounds in order to compress, low & hi cut and make use of sidechain compression.

A general rule would be to try and roughly mix as you go along as this helps at the end to complete the mix down. Don't be afraid to remove FX and processing from things as you go along and don't be afraid to replace things like the kick and snare further down the line .The amazing kick sound you had when you first created the beat might not cut it the further you progress with the track. Also it's always worth A-B'ing to a track you think is similar.

What production technique do you think is really overused / annoying?

Probably overuse of the bitcrusher. We do use it sometimes but more as a compressor or often used subtly to make things a little less clean. The classic crushed to death sound get used way too often in our opinion.

What do you know now that you wish you had known when you started out?

In terms of production there are too many things to mention! You don't really have to be the greatest technical producer to make good music. At the moment it's so easy and cheap to start producing music and there are so many great tutorials online that there is huge amount of tracks out there that 'sound' pretty impressive.

The most important thing is to be brave and try and create something original. It will really set you apart from the thousands of other demos that labels get sent and I think in general electronic music fans are always on the lookout to get behind some truly imaginative music.

Taken from here - http://www.kmag.co.uk/editorial/musicte ... matta.html

Bass music duo Matta have just released a sample pack called Dark Garage & Dubstep on Samplephonics. Read on to discover how they approach working in the studio and how you can win one of three packs we have to give away.

How do approach starting a new tune?

We pretty much always start with the drums in order to get a good groove and a solid foundation for the track. When we first started out producing, as soon as we had the drums working, we would always dive straight into the bassline as that has always been the most enjoyable part for us.

We found that a better approach is to build up some FX sounds, pads, drones, extra percussion - and in some cases a whole intro - to give the track a little bit more depth and a texture before attempting the bassline.

Do you usually wait till you're in the right state of mind before starting a track or do you just sit down and see what comes out?

It would be a luxury to always be in the right state of mind before starting a new track. We always try and get an idea of what we want to make before we start something new but sometimes we just jump in a see what happens.

It will often take longer to get something working but the results can sometimes be more interesting. We have banks and banks of synth presets we have made to use as a starting point too.

Does your approach differ depending on which genre you are making?

Not hugely in terms of the way we would build a track from the ground up. We'd still usually start with a beat but, in the case of a more chilled out track, we would definitely concentrate more on the overall soundscape and get some melodic elements first. In the case of a heavier track we would concentrate more on the bass and variations of it.

Out of the tracks you do start, how many get finished? How many get released?

It's difficult to say but probably around two tracks get started to every one we finish. We have quite a few unfinished tracks on our hard drive and if we are really stuck for inspiration sometimes we go back and have a look at half-finished projects as a starting point.

However, when we go back to tracks we make sure we really strip them down in order not to end up having the same problem of not being able to finish it again.

What do you do when you're not feeling inspired?

Other than going back to half-finished projects, it's mainly simple things like doing anything else, going for a walk, listening to some tracks from other artists we like or even to listen to music outside of the genre to clear the palate.

There is always things we can do like, play around with a synth and see what it is capable of, make some new sounds, organise sample libraries, etc. Days where we lack inspiration is always a good opportunity to catch up on listening to promos we get sent too. There is also Countdown and Deal Or No Deal!

Where is your studio set up and what does is consist of? Do you use any hardware or are you software only?

The studio is set up at home and it consists of a Mac desktop, Focusrite Sapphire, a pair of Behringer controllers (BCR & BCF 2000s) and a Novation Xiosynth. We work pretty much solely in the box. We often record found sounds through a mic or onto a recently purchased Zoom h4n to include in our tracks. We have a few banks of random percussion and sound effects made this way.

What's your most used plugin?

Probably sample delay. We use it a lot on our FX and percussion parts. If you delay the left or right signal by about 600 - 800ms the sound appears a lot wider which helps with bringing things out of the mix.

Another plugin we use a lot is the Tone2 filterbank. It's got some quite unusual filter types and we use it to either completely change the shape of a sound or subtly add movement to it. Also we love the Reaktor Space Master reverb because it can be used to both create space and mangle sounds.

Are you the sort that likes to use old vinyl to get snippets of atmos, FX, melodies, etc or do you use synths mainly for your sounds?

We mainly use synths and try and sculpture things from scratch to try and give it an individual sound. We have been known to get out microphones and sample various things which can be really interesting once you clean them up and apply some crazy effects to them. The only sampling we have ever done from vinyl is from old battle records where you can get some nice snippets of vocals or stabs which can sit in the background of a track and build an atmosphere.

What's the coolest bit of kit you own?

Without doubt it's the Korg Monotron. We've never used it for a bassline but it's quite fun to mess around with and record weird effects and riser sounds into the sequencer. There are other bits of slightly more sophisticated equipment we've had access to but the immediacy and simplicity of the Korg makes it the coolest.

What's the best piece of equipment you've ever used?

A friend of ours had a Novation Bass Station which was a lot of fun to mess around with. We've never used one on a track but for sheer hands-on fun you couldn't beat it.

Which sequencer do you use and why?

We use Logic and have done for some time now, but we rewire it with Ableton to use the time stretching and sampler functions. Ableton handles that stuff so much better than Logic. I actually think the way things are handled in Ableton makes the workflow very good but we still prefer the Logic environment and the standard plugins that come with it.

A lot of producers we know have made the switch to Ableton but we are so comfortable with using Logic that it's hard to justify changing when we can use the best bits of both programs using Rewire.

What’s your monitoring situation like? What speakers and / or headphones do you use?

We have a pair of Genelec 8020's with a Genelec 5040 sub. When we are on the road we just use the headphones we are most familiar with the sound of - which happen to be a pair of cheap Phillips in ear headphones - but we always do the mixdown in the studio as they are nowhere near accurate enough for detailed mixing.

Any advice you can give us regarding mixdowns?

Firstly, we always try and put a bit of time between finishing the track and mixing it down. That really helps us notice things that we may have just got used to when writing. Always low cut things to leave enough room for the sub and hi cut things to make room for things like percussion, hats and rides.

Also, we never mix with any limiters on the master. We also like bussing all our drums together to process. compress and effect as a whole and we usually do the same with bass sounds in order to compress, low & hi cut and make use of sidechain compression.

A general rule would be to try and roughly mix as you go along as this helps at the end to complete the mix down. Don't be afraid to remove FX and processing from things as you go along and don't be afraid to replace things like the kick and snare further down the line .The amazing kick sound you had when you first created the beat might not cut it the further you progress with the track. Also it's always worth A-B'ing to a track you think is similar.

What production technique do you think is really overused / annoying?

Probably overuse of the bitcrusher. We do use it sometimes but more as a compressor or often used subtly to make things a little less clean. The classic crushed to death sound get used way too often in our opinion.

What do you know now that you wish you had known when you started out?

In terms of production there are too many things to mention! You don't really have to be the greatest technical producer to make good music. At the moment it's so easy and cheap to start producing music and there are so many great tutorials online that there is huge amount of tracks out there that 'sound' pretty impressive.

The most important thing is to be brave and try and create something original. It will really set you apart from the thousands of other demos that labels get sent and I think in general electronic music fans are always on the lookout to get behind some truly imaginative music.

Taken from here - http://www.kmag.co.uk/editorial/musicte ... matta.html

Re: Thinking out loud...

In The Studio: Sleeper

Dubstep producer Sleeper is best known for his heavy tunes on labels like Chestplate but his latest release is a bit different, a sample pack called Dubstep Beats & Bass Volume 1 that does exactly what it says on the tin.

How do you approach starting a new tune?

I spend a lot of time designing sounds and building sample packs so when it comes to starting a new track I have a huge amount to draw from. Sometimes I won’t start a track for a month or so and just build sounds non-stop.

I've been working like this for a while now and find it really pays off when it comes down to putting a track together, ideas can flow much quicker when you don't have to spend too much time on each sound as you go.

Do you usually wait till you're in the right state of mind before starting a track or do you just sit down and see what comes out?

I spend most of my time working on music and that time is usually split into either building a track or designing sounds. When I'm in the right state of mind and feeling creative I'll work on a track and when I'm feeling less inspired I'll be building a library of sounds or making synth patches and effects chains so when that creative state of mind comes, I’ve got loads of fresh sounds to use and I can get my ideas out quickly.

Does your approach differ depending on which genre you are making?

Yeah, kind of, only when it comes to sound selection though really. When I'm making more techno sounding stuff I like to use more distorted, crunched up sounds and dirty textures, so the sound designing beforehand would have also been approached differently in order to get those kind of sounds.

Things like arrangements have to be approached differently too, I've started doing a lot of live arrangements over the past year or so which I got into through writing techno.

Out of the tracks you do start, how many get finished? How many get released?

It's changed a lot over the last few years since changing my approach to production; the sound design stuff helps massively. Years ago the majority of my ideas would never get finished but now most of them get finished properly and released in some way or another and I think it's all down to having my sounds ready to go when I come to make a track.

What do you do when you're not feeling inspired?

I don't believe in writers block. I think that whatever your art is, there's always something that you can be doing. Whether it’s designing sounds, making a sample pack, going to your local record shop and looking for samples or just learning something new, there's always something that you can be doing that can go towards a final product.

Also, I always find that if I'm not feeling inspired enough to start a track, all I do is make some fresh sounds without the pressure of actually writing a track, then before you know it you're buzzing off some new sound you just made and a track ends up coming out of nowhere.

What does your studio consist of?

My set up has always been really basic, I bought a few nice Akai MIDI bits last year for recording live arrangements but other than that it's just my PC running Live 9 and Cubase.

What's your most used plugin and what makes it so essential?

Fab Filters Pro Q EQ plugin gets used on every sound I use so I would have to go with that one. For synths I'd have to say Ableton’s Operator, it's really powerful and also really easy to pick up once you have a decent grasp of frequency modulation. I've been getting my head around it for the last eight months or so and use it for about 90% of my stuff now.

Are you the sort that likes to use old vinyl to get snippets of atmos, FX, melodies, etc or do you use synths mainly for your sounds?

I used to sample a lot of old soul and jazz years ago when I was making drum & bass but I've not sampled a thing for a couple of years now, so at the minute I'm pretty much 95% synths and effects. I do love doing it that way because I know all my sounds are completely original and I like seeing a whole track emerge from the same four oscillators, but at the same time I do miss the digging.

What's the coolest bit of kit you've got and do you actually use it much?

I don't really have much kit but my Akai APC is pretty cool and I use it on every track now. It's basically like having a full size mixing desk for your Ableton projects, which is great for recording live arrangements as well as sound design. I'm definitely getting the new version when it comes out, I might even get two. I'd recommend them to anyone looking to add a more human feel to their arrangements.

What's the best piece of equipment you've ever used?

Technics 1210s.

Which sequencer do you use?

I'm using Ableton and Cubase. I've always used Cubase but after trying Ableton last year I now only use Cubase for the final mix downs and spend most of my time on Ableton. I find it a lot more geared toward creativity, everything from effects chains and routing to sample swapping and editing all seems so much faster and more fluent in Ableton, especially with a good midi set up.

The midi stuff is so easy to use that you can take things to a more complex level with sound design and effects automation on arrangements. Cubase seems so stale and robotic in comparison but I much prefer the sound engine and mixer on it which is why I still use it for my final mixes.

Any new studio technology or gear you like at the moment?

I don't really have much studio gear but I picked up the Korg Monotron Duo and Delay about a month ago and have got a lot of use out of them so far.

What’s your monitoring situation like?

Pretty bad to be honest. I've just got Alesis M1 Actives, they are pretty much the cheapest monitors you can buy and they have recently starting making a very strange high pitched crackling sound so I think I'm due an upgrade.

Any advice you can give us regarding mixdowns?

If I'm honest, I'm not really the best guy to ask about mixdowns, it's easily my weakest area in production and the part I enjoy the least. One thing I would say though is to just try and mixdown as you go, making sure each sound is how you want it before moving on to the next. Also space in the mix is some pretty basic advice, giving each sound its own frequency range and space allows them to really stand out.

What production technique do you think is really overused / annoying?

At the moment it's got to be that percussive hit that all the big 'EDM' guys are using in triplets, you know the one.

What do you know now that you wish you had known when you started out?

I think that has to be the sound design thing. Years ago I never realised how beneficial it is to sit and make sounds before you start a track. I think I would have saved a lot of time if I had started doing it from the beginning.

Taken from here - http://www.kmag.co.uk/editorial/musicte ... eeper.html

Dubstep producer Sleeper is best known for his heavy tunes on labels like Chestplate but his latest release is a bit different, a sample pack called Dubstep Beats & Bass Volume 1 that does exactly what it says on the tin.

How do you approach starting a new tune?

I spend a lot of time designing sounds and building sample packs so when it comes to starting a new track I have a huge amount to draw from. Sometimes I won’t start a track for a month or so and just build sounds non-stop.

I've been working like this for a while now and find it really pays off when it comes down to putting a track together, ideas can flow much quicker when you don't have to spend too much time on each sound as you go.

Do you usually wait till you're in the right state of mind before starting a track or do you just sit down and see what comes out?

I spend most of my time working on music and that time is usually split into either building a track or designing sounds. When I'm in the right state of mind and feeling creative I'll work on a track and when I'm feeling less inspired I'll be building a library of sounds or making synth patches and effects chains so when that creative state of mind comes, I’ve got loads of fresh sounds to use and I can get my ideas out quickly.

Does your approach differ depending on which genre you are making?

Yeah, kind of, only when it comes to sound selection though really. When I'm making more techno sounding stuff I like to use more distorted, crunched up sounds and dirty textures, so the sound designing beforehand would have also been approached differently in order to get those kind of sounds.

Things like arrangements have to be approached differently too, I've started doing a lot of live arrangements over the past year or so which I got into through writing techno.

Out of the tracks you do start, how many get finished? How many get released?

It's changed a lot over the last few years since changing my approach to production; the sound design stuff helps massively. Years ago the majority of my ideas would never get finished but now most of them get finished properly and released in some way or another and I think it's all down to having my sounds ready to go when I come to make a track.

What do you do when you're not feeling inspired?

I don't believe in writers block. I think that whatever your art is, there's always something that you can be doing. Whether it’s designing sounds, making a sample pack, going to your local record shop and looking for samples or just learning something new, there's always something that you can be doing that can go towards a final product.

Also, I always find that if I'm not feeling inspired enough to start a track, all I do is make some fresh sounds without the pressure of actually writing a track, then before you know it you're buzzing off some new sound you just made and a track ends up coming out of nowhere.

What does your studio consist of?

My set up has always been really basic, I bought a few nice Akai MIDI bits last year for recording live arrangements but other than that it's just my PC running Live 9 and Cubase.

What's your most used plugin and what makes it so essential?

Fab Filters Pro Q EQ plugin gets used on every sound I use so I would have to go with that one. For synths I'd have to say Ableton’s Operator, it's really powerful and also really easy to pick up once you have a decent grasp of frequency modulation. I've been getting my head around it for the last eight months or so and use it for about 90% of my stuff now.

Are you the sort that likes to use old vinyl to get snippets of atmos, FX, melodies, etc or do you use synths mainly for your sounds?

I used to sample a lot of old soul and jazz years ago when I was making drum & bass but I've not sampled a thing for a couple of years now, so at the minute I'm pretty much 95% synths and effects. I do love doing it that way because I know all my sounds are completely original and I like seeing a whole track emerge from the same four oscillators, but at the same time I do miss the digging.

What's the coolest bit of kit you've got and do you actually use it much?

I don't really have much kit but my Akai APC is pretty cool and I use it on every track now. It's basically like having a full size mixing desk for your Ableton projects, which is great for recording live arrangements as well as sound design. I'm definitely getting the new version when it comes out, I might even get two. I'd recommend them to anyone looking to add a more human feel to their arrangements.

What's the best piece of equipment you've ever used?

Technics 1210s.

Which sequencer do you use?

I'm using Ableton and Cubase. I've always used Cubase but after trying Ableton last year I now only use Cubase for the final mix downs and spend most of my time on Ableton. I find it a lot more geared toward creativity, everything from effects chains and routing to sample swapping and editing all seems so much faster and more fluent in Ableton, especially with a good midi set up.

The midi stuff is so easy to use that you can take things to a more complex level with sound design and effects automation on arrangements. Cubase seems so stale and robotic in comparison but I much prefer the sound engine and mixer on it which is why I still use it for my final mixes.

Any new studio technology or gear you like at the moment?

I don't really have much studio gear but I picked up the Korg Monotron Duo and Delay about a month ago and have got a lot of use out of them so far.

What’s your monitoring situation like?

Pretty bad to be honest. I've just got Alesis M1 Actives, they are pretty much the cheapest monitors you can buy and they have recently starting making a very strange high pitched crackling sound so I think I'm due an upgrade.

Any advice you can give us regarding mixdowns?

If I'm honest, I'm not really the best guy to ask about mixdowns, it's easily my weakest area in production and the part I enjoy the least. One thing I would say though is to just try and mixdown as you go, making sure each sound is how you want it before moving on to the next. Also space in the mix is some pretty basic advice, giving each sound its own frequency range and space allows them to really stand out.

What production technique do you think is really overused / annoying?

At the moment it's got to be that percussive hit that all the big 'EDM' guys are using in triplets, you know the one.

What do you know now that you wish you had known when you started out?

I think that has to be the sound design thing. Years ago I never realised how beneficial it is to sit and make sounds before you start a track. I think I would have saved a lot of time if I had started doing it from the beginning.

Taken from here - http://www.kmag.co.uk/editorial/musicte ... eeper.html

Re: Thinking out loud...

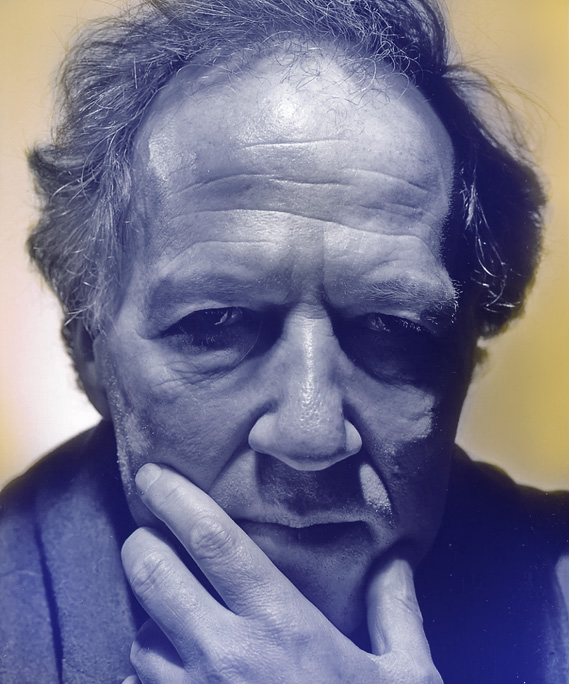

“If I wanted an easy life it wouldn’t have been with music”: The Bug interviewed

Kevin Martin is a master of what he calls “future shock reinventions”.

He’s been musically mutating since the ’90s, spending that decade in experimental groups God, Ice and Techno Animal, the last a duo with Justin Broadrick, before introducing the alias The Bug in 1997. Tapping the Conversation, an abrasive hybrid of dub and hip-hop made in collaboration with DJ Vadim, was the first full length under that name, and was followed by a series of The Bug vs Rootsman singles on Razor X a couple of years later. But it was Pressure, released on Rephlex in 2003, that brought the solo incarnation to wider attention, with vocal collaborations with Daddy Freddy and Roger Robinson that demonstrated beautifully Martin’s knack for incorporating different voices into his blueprint without surrendering his own.

Five years later, Martin released London Zoo on Ninja Tune. Perhaps unfairly, it was lumped in with the wider dubstep trend of the time, although its rhythms drew on grime, dancehall, dub and industrial. More focused on songs than Pressure, it featured vocalists on nearly every track – with two songs in particular that grew ubiquitous in the UK underground, reaching a near-mythical status: ‘Poison Dart’ with Warrior Queen and ‘Skeng’ featuring Flowdan and Killa P. In 2008 too, King Midas Sound, Martin’s group with vocalists Kiki Hitomi and Roger Robinson that fused dub, lovers’ rock and the more aggressive side of shoegaze, released a single on Hyperdub, and Waiting For You the following year.

That Martin is prolific is beyond doubt. But despite more new solo material in the interim between London Zoo and now – a clutch of Acid Ragga 7-inches and the Filthy EP – Angels & Devils is the first Bug LP in nearly six years. It’s also Martin’s most ambitious to date, and not just because he moved from London to Berlin and widened his narrative scope to include not just the megalopolis, but also what lies above and below. Much like its title, the sequencing of Angels & Devils’ at first seems unusually conventional for Martin, with a softer ‘Angels’ half backed with a fearsome ‘Devils’ side. Yet Martin’s aim is not to distort the dualities of good and evil or ascension and decline that constitute much of the album’s thematic material, but, he says, to represent the place “where those polar opposites collide”.

His choice of collaborators, from Justin Broadrick and Miss Red to Grouper and Flowdan, mirrors that ambition. Few would attempt to make an album featuring Roll Deep’s Manga and Warrior Queen alongside Inga Copeland, Death Grips and Gonjasufi, and fewer still could make such an album cohere. But Angels & Devils, which opens with Grouper’s otherworldly vocals and closes with Flowdan’s tirade against politicans and fast food on ‘Dirty’, was written with vocalists in mind. That keen attention to the collaborators’ individual voices, along with a narrative arc that charts decline and decay, give it a solidity unexpected in a record so varied. Though Martin literally corrals the dual aspects of angels and devils onto the two sides of the record, there’s ambiguity at work, too. Tracks like ‘Fat Mac’ and ‘Dirty’, both of which feature Flowdan, may be the height of toughness on the ‘Devils’ side, but ‘Angels’ songs ‘Void’ and the towering ‘Ascension’ instrumental are sweet yet sick at heart – beautiful, but rotten with infection.

After London Zoo and your work with King Midas Sound, what did you feel you wanted to do with The Bug?

I realised recently that there is a sort of overlap in some ways between King Midas Sound and The Bug and the work I’ve done for them both. I didn’t really go into this album thinking I wanted to sweeten up the sound of London Zoo, for instance. It was primarily that I wanted to stretch the parameters of London Zoo in both directions simultaneously. I wanted it to be more beautiful on one hand, and more ugly on the other, and I think it was a case of having to come to a decision whether I wanted to completely jettison my previous sound, or to continue and try and craft what I’d already done.

There was a bit of soul searching because every sentence seemed to be dubstep this or dubstep that for journalists or people I met, and while I have many friends in that area and it helped me, I just never felt comfortable with being perceived as a dubstep artist. So it was like, what do I do here? Do I just say “fuck it” and lose all the work I put into London Zoo? The more I thought about other artists that I liked, the more I realised that it always feels more successful and more honest when artists continue a direction they’ve begun with, rather than completely cancel out the sound they were synonymous with. I felt it would be a bit fraudulent and also just a bit reactionary on my own part to say, “Fuck it, I’m doing something totally different”.

It seems like the increased interest in dubstep at the time was a bit of a happy coincidence for London Zoo.

I was really fortunate to have dropped that album at a time when there were some very, very talented producers suddenly coming into play, and for sure a lot of those producers became very good friends, and I had and have a lot of admiration for them. Any scene or any collection of producers that can include people as varied as Kode9, Burial, Shackleton, Mala, Coki, Jamie Vex’d — that’s crazy in itself. It’s just I always feel like a bit of a lone wolf, I never feel happy in a herd mentality. The artists I have the most respect for probably exist in their own void, too. They come to terms with their own sound, and I can spot the sound that that particular artist will make within seconds. That’s what I admire and what I attempt.

It just felt strange, partly because what dubstep became is pretty hideous anyway, and also because it doesn’t fit me, which anyone who listens to the records will realise. There was a lot of criticism among dubstep fans that there were too many vocals on London Zoo, or too many different tempos, or whatever. For me, that’s just ridiculous. I’m very vocal-oriented and I value freedom of thought and freedom to move.

I’d like to talk a bit about Justin Broadrick. He’s really the epitome of an artist who can move between different projects while retaining a sound that’s definitely his own. You’ve worked with him pretty much from the start. What impact would he say he’s had on your work over the years?

I wouldn’t be producing if it wasn’t for Justin. He was a massive influence on me at the very beginning of our friendship. I even asked him to produce my first band, because I was so impressed by the sound of the first two Godflesh albums. We also just got on like a house on fire, like brothers from another mother. There was a lot in our backgrounds that seemed to culminate in us both needing music as a therapy. If you spoke to him, I’m pretty sure he would say the same thing as me: we didn’t make music to make cash, we didn’t make music to become famous; we did it because we had no other choice. It was about our only escape route, and I think Justin is as free-willed as I am. In all the years I’ve worked with him, I can only remember us having one miniscule argument, which is ridiculous when working with someone for that long. But I think I recognise in him the same need for the shock of the new, the same need to reinvent yourself to keep yourself interested, and just that passionate urge to connect with sound, and to need sound as a catalyst to navigate this fucked up world.

Of course, there’s stuff we don’t agree on. It made me feel nauseous when he was enjoying bands like Oasis, or insisting on watching Headbangers Ball from beginning to end – after about fifteen minutes I would be begging him to turn it over to Yo! MTV Raps or whatever. When I started The Bug, I was just shitting myself, thinking, am I going to be able to do anything worthwhile outside of Justin’s shadow? I thought I really had to find my own voice, and craft my own image. So of course there are divergences, but our instincts, our philosophy and our aesthetic are definitely very similar.

You say music was necessary as a therapy for both you and Justin. Is that the philosophy you share?

Music is a catharsis for release, or a life force. Having faith in music is unfashionable in these days of giveaway, throwaway tracks. But I think we both thought that music was revolutionary in our lives, and we still want to have an impact. We still cherish a record. I’m still hooked on buying reggae 7-inches and I’m still every bit as excited about discovering some new producer who’s got a sound that makes me say “What the fuck?!” Fundamentally, music is still my life. I used to think it was a means to bury myself in the reality of everything, but increasingly I’ve realised it’s really a parallel universe for me that I’ve been constructing, because the real one is just too much.

There’s a real duality to it. In a lot of ways I felt music’s fulfilled all my dreams but it’s also led to lots of other problems along the way. If I wanted an easy life or to make money it wouldn’t have been with music, so there’s the positive and negative, and the collision of the two.

Did that collision between positive and negative inspire the themes of Angels & Devils?

I remember making an almost throwaway comment to Ninja Tune, telling them that I want to bring in more angels and devils in connection to London Zoo. The more I thought about the title, having come from a throwaway idea, the more it made sense for so, so many reasons, even though it’s a very traditional title that goes back to classic literature and painting and so on.

How did the title make more sense as the album developed?

It was never going to be an album sequenced with two opposing sides; that came much later in the making of the record. I think it’s an admission that we all have to struggle with the opposites in ourselves. I’ve been told I’m a classic Gemini, so maybe I’m even more at war with my own personality. The more I probed the idea of how far I could stretch what I’d done before, the more obvious it seemed that this record was about contrast, contradiction, and the points at which polar opposites meet, inasmuch as there are devils in angels, and angels in devils. One person’s heaven is another person’s hell. All those things became very interesting to me over the course of making this record.

Yes, there’s plenty of bleakness and horror in the “Angels” side of the record, too.

We all want to believe in black and white; we all hope that life is black and white because then it’s readily understandable or navigable. But primarily, it’s the kaleidoscopic mess of colour everywhere that fucks everyone up, and the sheer chaos that surrounds us all that makes it hard to determine where the angels are and where the devils are.

The decision to split the album down the middle seems almost counter to that idea.

Ninja weren’t too happy about that decision, they thought it might be the wrong move. But when it came to actually compiling the tracks, it’s always been a case of me trying to find a narrative as I go along, or trying to understand my own narrative ambitions throughout the making of a record. I think my enjoyment of music is totally polarised. I realise it’s the middle mass music that does nothing for me, and that sheer functionality or disposability is the enemy. I have two needs that I want to satisfy with music. On the one hand, I genuinely want music that I can use as sonic warfare, or to go to a club and have my head completely destroyed by an insane frequency assault. On the other hand, I want to listen to shit at home that transports me elsewhere without necessarily being antagonistic.

That goes back to what you were saying about there being a bit of overlap between The Bug and King Midas Sound. Do you see the projects informing one another?

Well, Roger’s forever trying to pinch Bug tunes for King Midas Sound! And King Midas Sound is really a very democratic group; we argue like fuck about everything. That’s the difference: as The Bug, I take collaborations with vocalists very seriously and hold them in the utmost respect, but it’s still very much my world. I still see it as my solo project, and I’m answerable to no one. King Midas Sound is based around songs and songwriting, and The Bug has become much more centred towards songs, but it’s still more deviant than that.

Was it working with King Midas Sound that re-oriented The Bug towards a stronger focus on songs, or something else?

It’s really just been about learning from mistakes. And I’m just being fucking greedy! Just obsessed with wanting everything from music. Why should I limit myself to just freeform analogue noise, or a functional club track? Why can’t I have everything in a track, why can’t I be completely overwhelmed and knocked out, as the best music does to me? That’s the ambition — not to say in any way that I’ve achieved that, but I’d rather have that ambition than settle for something flat in the middle ground.

Given all that, it must have been on some level frustrating when people said your music was dubstep around the time of London Zoo.

To be honest, yeah. And I don’t know where it came from, but the whole “bass music” thing. What the fuck is that? The best music always had shitloads of bass – my first band had three bass players in it! But that’s not enough. I love the idea of bass and space, but I always want more.

That’s the thing; I always hold an album dear even though at the moment there’s a very valid argument for just concentrating on just one smash YouTube tune after another and never giving a fuck about albums. That’s an exhilarating approach as well, but for me personally as The Bug, I like the idea of a strong narrative flow to a record, and everything about the record being connected: the artwork, the thinking behind it, and the choice of who to work with vocally. The artwork was crucial; the choice of vocalists was crucial; song titles are very important. It’s a total package, not settling for some half-arsed, throwaway product, because God knows that’s the problem with the music industry by and large. It’s so easy to make music now, easier than it’s ever been, so how can you do something that has any resonance and justification for its existence. I punish myself by wondering about this shit all the time. I should lay off and chill the fuck out, though I guess if I could I’d be making other forms of music.

“Bass music”, probably. What shaped the narrative as you wrote the tracks and compiled the album? As the album progresses from the ‘Angels’ to the ‘Devils’ side, you get this sense of decay and decline.

Once I decided to sequence in two halves, there was actually discussion of whether or not to start with the intense side and end on a positive note. God knows I’m always fighting my own impulses. I feel personally I’m a very positive person, though most people will listen to my shit and come across me as being very intense. I guess I’m seen as being difficult because I’m trying to be a perfectionist when it’s not fashionable to be so, and I think that I always seem to have alternated between great positivity and misanthropic, nihilistic, everything’s fucked mode. And this record is an acknowledgment of that. Throughout the course of this record, very key things happened. I became a father for the first time while finishing the record, and undoubtedly that had an impact on me psychologically.

And how did that affect what you were doing artistically?

Again, it would be two opposite reactions. On the one hand I was shitting myself with the responsibility of having brought another person to this planet, but on the other hand just saying, wow, this is an incredible thing. Having spent my whole life running away from the idea of being a father to suddenly being in that position has obviously had a massive impact. It’s hard to say creatively how that’s worked, but it made me all the more certain that I wanted some sense of beauty in this record, and some sense of utopian longing.

So the warfare relates to very personal battles really, with yourself.

Undoubtedly. I always think I’ve fucked it up, whichever record really. I remember after London Zoo I literally shed some tears when I got home from mastering and back to the studio where I was living at the time and thought, “Wow, who’s going to give a shit about this, it’s just a flat piece of nothingness.” And I really felt that.

With this record, after I’d done it, I realised that this really doesn’t fit in anywhere. It really doesn’t. Whenever I’m asked what my music sounds like, I’m like, how the fuck do I sum it up? I just know that I’m an enemy of my own lust for creating something as individual as I possibly can, and I know I always want to hear shit that I’ve never heard before. When something I’m doing becomes overly familiar, I’ll scrap it and try again. Many of the tracks on Angels & Devils are rewritten again and again. For instance, the tracks with Liz Grouper: the sketches she was sent are totally different from the tracks that ended up being produced. I had initial sketches which I wrote with her in mind, and when I got her voice back, it made me rethink my initial approach and want to try and better my part of the collaboration. That’s the thing. The people I chose to work with on Angels & Devils are incredible voices in their own right, and it does add to the pressure. I don’t want those people to be ashamed of having collaborated with me.

The collaboration with Liz is one of the most unexpected on the record. How did you decide you wanted to work with her?

I was obsessed by her records, I thought they were incredible, the Alien Observer album in particular — it’s just mindblowingly good. She was realising an emotional area that I wanted to free up for this record. The reviews for the Filthy EP were really mixed. Some were saying that this is the same old Bug shit, basically, and for me that seems strange, because working with Danny Brown on a Bug track, or incorporating elements of corroded brass, seemed very different to me. But I was even more determined that I wanted to come with the fresh shit that people wouldn’t expect on this record.

I think Liz strives for a real spirituality. Her music and how her vocal carries tracks seems to radiate an alien spirituality. It’s elusive but warming at the same time, and she very much has her own voice. Nearly everyone I approached on this album to collaborate with, I felt we’re all fellow freaks. All seemingly following a path of finding and crafting their own artistic voice. And she just really fitted that bill. I wouldn’t know personally where she fits in the bigger scheme of things, but I just knew that emotionally there was something that attracted me to working with her and seeing an amazing potential for the sort of sonic environment I could construct around such an incredible voice.

There’s definitely an outsider quality that unites many of the artists you’ve chosen for the record – a pack of lone wolves, as it were. It’s interesting what you say about Grouper being very spiritual, because having her on the same record as Gonjasufi really brings out the parallels between them that perhaps aren’t obvious.

There are similarities to them both that are very evident to me. I think that with both their voices, some people might find them very beautiful and other people might find them incredibly sad, but that was the attraction to working with voices with that duality. On the other hand, people like Manga and Flowdan are synonymous with grime, though I know Manga’s tried to break out from that, and Flowdan too in a strange way. Much as he continually talks about being a grime artist and grime being what he does, I think he’s already surpassed that in terms of his development as an artist. I feel like Mark [Flowdan] has broken out from the comfort of being in Roll Deep to becoming an incredible solo MC. So as much as I’m fine to be referred to as a freak, if the guests I invited to be on this record weren’t, I would say they’re highly individualistic.

It says a lot for your own sound that tracks featuring such a wide range of artists can all sit alongside one another and the album make sense as a whole.

That’s the challenge; how can this be a Bug album and not be seen as a compilation? That was something in the back of my mind throughout the making of it. It still had to have a feel I felt was personal, even though it was dealing with strangers. It was a challenge I loved. The vocalists that I approached all agreed to be on here because they were supportive of previous records I’d done, which was an amazing thing for me, because these are people I have maximum respect for, and it was very humbling that they wanted to participate just because they trusted me from previous records.

The tracks interrelate lyrically, too: Inga talking about civilisations and relationships disintegrating on ‘Fall’, and then the realisation of that decline on ‘Fat Mac’ and ‘Dirty’.

When Ninja Tune was suggesting which tracks to run into the album, in terms of teasing or streaming, whenever I isolated tracks I thought they were cool, but somehow it made more sense to me inside the whole album. They’re all parts of a whole.

The design of the artwork and atwarwithtime.com seem to tie into the music strongly, too. How did you conceive of the whole visual aesthetic?

It was really working with Simon Fowler that was key to this. He’s an illustrator who’s become a good friend. He’d previously worked with Earth and Sunn O))) and co-founded the Small But Hard label in Berlin. Kiki Hitomi introduced him to me at a Goblin show. He’s sort of sickening, really, because everything he turns his hand to is amazing. He speaks fluent Japanese; I’ve heard he’s an incredible sushi chef; he’s an amazing illustrator and an incredible printmaker. I think illustrators and designers find me hell to work with because of the perfectionism. I feel that the artwork has got to reflect what I feel I’m doing with the music, and once you start straying away from that… He could have said “fuck you”, but there was a vision we both wanted to pursue with this record. There were all sorts of benchmarks I threw at him, from Hieronymus Bosch to extreme Japanese illustrators to books on logos of terrorist organisations, and he managed to reel all that in and just do incredible work, not only on the sleeve itself but on the logo and font too. There are going to be other things following the album that will carry on the visuals.

Such as your collaboration with Dylan Carlson.

I’m madly excited by the collaboration with Dylan. Ninja Tune were the ones who said that the tracks stood really well in their own right, and they might get lost if they were on the album because some people don’t value instrumentals. And it’s a really exciting collaboration because I think it’s going to be ongoing. I think we’re going to do live stuff together, he invited me to do dub mixes of the early Earth recordings, and I’m a great admirer of his work. Weirdly enough, considering I have a sort of love-hate relationship with guitars, it’s fantastic to work with a guitarist I have so much respect for, and vice versa.

Why the love-hate relationship with guitars?

My mother used to have speakers in very room in the house, and she used to pipe Deep Purple, Rainbow, Santana, Led Zeppelin – just a whole host of musical war criminals – into my consciousness, and it meant that guitars for me were just horrible. It seemed like everything that I listened to for years was guitars, and I guess that’s why I gravitated towards post-punk as a kid. I just wanted space in music, because the exhibitionism of all the guitar music she used to play was just repulsive to me. It almost threw me off guitars for a long time. Then that whole explosive post-punk mindfuck – people like PiL, or The Birthday Party, or Joy Division, or Throbbing Gristle, or Crass, or 23 Skidoo, or Cabaret Voltaire – these were all the artists that inspired me to make music as a young kid, and they were sort of anti-rock’n'roll, I suppose.

Post-punk wasn’t just a musical thing. Because that was a difficult time for me in life, it just addressed my relationship to society, to family, to the world. I grew up in a pretty unfashionable town way away from the live circuit, and John Peel was my lifeline. For me, post-punk was as much about the people involved in it. They seemed to promote the idea of questioning everything, believing nothing, and using paranoia as a tool of dissemination of social constructs. To chase every dream you have, to trust no one along the way, and to see the industry as your enemy. Those are just a few things I can think of off the top of my head that I felt were ignited by some of the great thinkers of that scene. Most of them were very heavily inspired by dub and reggae, too.

Dub has been hugely important to all your projects, I think. Why did it initially appeal back in the days when you were listening to John Peel?

I think that my attraction to dub was that you could just open up a track as opposed to closing it with multi-track layers of mid-range guitar. Deep dub was sort of inescapable if I was into the sort of crazy shit I was into. I remember very vividly that a very good friend of mine who was considerably older than me took me to his lecturer from college to smoke weed, and they put on a Prince Far I track called ‘Foggy Road’, which isn’t a dub track, but it’s a deeply smoked-out track which just sounded like some alien transmission from another planet. I grew up in a seaside town that was like a miniature version of Brighton, which was whiter than white, and just to have this unfiltered, deeply psychedelic reggae track played to me had a big, big impact. I remember it very well to this day.

Discovering stuff like On-U Sound, King Tubby and Lee Perry at pretty much at the same time was just mind-warping. I was just, like, wow: tracks can be really turned inside out, upside down and back to front, and still lead you into a real unknowable unknown — a musical void, in the best sense. From then, really, it was just that love of reggae’s constant yearning to renew itself and have future shock reinventions. I became more and more fascinated by dub as a philosophy as much as a musical tool, or as much as a way of helping tracks avoid their sell-by date. I saw echoes of dub in the writings of William Burroughs or in the films of Jean-Luc Godard, with their crazy edits, or in lots of different areas of art, not just music.

Dub is metaphorically a sickness, too.

It’s a means of infection. I did a compilation for Virgin called Macro Dub Infection, because I thought of the viral spread as it infected all different genres and areas, and infected people’s brains and imaginations in a great way — potentially.

Speaking of On-U Sound, wasn’t there going to be a Bug collaboration with Adrian Sherwood?

There was, and that happened during the course of not really knowing what I was going to follow London Zoo up with. My first instinct was to do dub versions of London Zoo, because I’d never done a proper, dedicated dub album, and I’d become very friendly with Adrian, who’d been very supportive of me down the years, so it felt like it would be a great thing to try. ‘Catch a Fire’ was the first track that was ready to be dubbed out by Adrian and me. In the mean time, I spoke to very close friends who I trusted to find out what they wanted to hear. Would they want to hear a follow-up to London Zoo, or would they want to hear London Zoo in dub, and it was just unanimous: people said, I want to hear a new album, not reinterpretations of an old one. I wish I could clone myself into a Dub Bug to just do dub mixes of my tracks all day. I’d love it.

Going back to collaborators on Angels & Devils, you’d obviously worked with Justin before, but how was it working with Warrior Queen and Flowdan again? Did you wonder where you could go with them after ‘Skeng’ and ‘Poison Dart’ had had such a massive impact?

‘Fuck You’ was actually an odd circumstance, because Warrior Queen had recorded that track at my studio for her solo album, and Kode9 had written a rhythm for it. But she and I had sort of fallen out after the making of London Zoo, and we hadn’t been in contact for a long time. She contacted me and said she really wanted to meet, and we just had this big hug and apology session. I said, it’s all cool, but I want to put ‘Fuck You’ on my album. And she very graciously let me work that vocal. It was always my favourite vocal by her. And it was one of the hardest tracks on this album for me to realise because there were so many versions. Kode9 had done a killer version, and I felt her vocal was so good that whatever I did musically was never going to really better what she had done.