The first thing to remember about music theory is that generally, if it sounds right, it probably is. There are no rules in music, and Music Theory is not about telling you how to write music. It's about understanding the music.

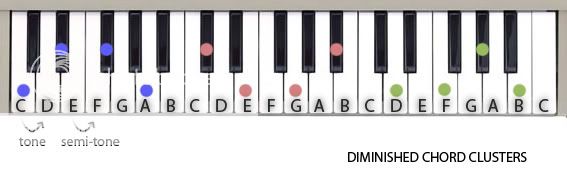

Broadly speaking, it is fair to say that most music is essentially based upon two crucial factors: scales and rhythm. Scales make up melodies, chords, harmonies and basslines to name but a few; whereas rhythm makes up the beat of the song. In this part of the Production Bible, you will learn the basics of Music Theory that will serve you not only in the production of Dubstep; but for any of your future musical pursuits. This information is intended to be easy to read and understand, so I won’t be mincing sentences. But firstly, please make sure you learn every single note on the keyboard by studying the image below. Otherwise you’ll be completely lost here.

Scales:

We’ll begin with scales. As I mentioned before, scales are the building blocks of your song; and without them, your track will be atonal and completely unlistenable (probably not the effect you’re going for!).

There are two main scales that you should learn inside out – the major scale and the minor scale. A generalisation you’re bound to have heard before is that the major scale sounds “happy”, and the minor scale sounds “dark”. Although this is not always the case, it is mostly true – and therefore you’ll usually be focussing on the minor scale when producing Dubstep. However, just in case you’re writing happy-dubstep (if that exists), here is a quick overview of both scales and how they are made up.

Major Scale:

The major scale is really easy to create. It is made by a single rule that is simple to put in to place:

“Tone, Tone, Semi-Tone, Tone, Tone, Tone, Semi-Tone”

In case you don’t know what a Tone or Semi-Tone is, here is a quick explanation:

Picture a keyboard (or if you can’t, see the image above.) Say you go from C to C#, that would be a semi-tone. The same thing goes for if you go from an E to an F – it is still a semi-tone, because you have gone up one key.

A tone is two semi-tones – for example from C to D is a tone, and the same goes for from G# to A#.

The scale’s name is taken from the note that it starts on. For example, C major will start on the note of C. Similarly, A major will start on the note of A, and this is the case with every single scale.

Here is a quick list of a few major scales. After having seen a few, try working the rest out for yourself in order to understand how the major scale is formulated. Ideally, you should practice your scales on a piano or keyboard so that you can physically see how to make the scale. It might sound boring, but it’s a small price to pay for a much deeper understanding of your music.

Note:

- E# is the same note as F, and B# is the same note as C

- If something has a ## it means it is sharpened twice (raised two semitones)

C Major: C D E F G A B C

C# Major: C# D# E# F# G# A# B# C#

D Major: D E F# G A B C# D

D# Major: D# E# F## G# A# B# C# D#

E Major: E F# G# A B C# D# E

F Major: F G A Bb C D E F

F# Major: F# G# A# B C# D# E# F#

G Major: G A B C D E F# G

G# Major: G# A# B# C# D# E# F G#

A Major: A B C# D E F# G# A

A# Major: A# B# C## D# E# F## G## A#

B major: B C# D# E F# G# A# B

Now, by arranging the different notes of each of these scales in any order you please, you can create a melody, bassline or harmony with extreme ease. Rearranging the notes in the scale will give you a flawlessly in-key result, and it is then up to you to use the notes in the scale as you see fit for your tune.

Minor Scale:

As was the case with the Major Scale, the Minor is made up from a set rule or formula. By knowing this formula, you can understand how the Minor is made, and how to use it to it’s maximum effect.

“Tone, Semi-Tone, Tone, Tone, Semi-Tone, Tone, Semi-Tone”

As is the case with the major scales, you should practice your scales as much as possible to make sure that you know them all like the back of your hand. Here are a few Minor Scales, see if you can work out the rest.

Note:

- E# is the same note as F, and B# is the same note as C

- If something has a ## it means it is sharpened twice (raised two semitones)

C Minor: C D Eb F G Ab B C

D Minor: D E F G A Bb C# D

F# Minor: F# G# A B C# D E# F#

G Minor: G A Bb C D Eb F# G

Similarly to the Major, now that you know your Minor Scales, you can quickly just take any note from the scale, rearrange it with another few notes in the scale, and there you have a fat melody or bassline ready to be played at maximum volume.

Diminished Chords:

Diminished Chords are really quite spooky and dark chords that are made up of four different notes; all a minor third apart from each other. That means that for example the Diminished Chord starting on C would be: C, Eb, F#, A, because to get from one note to the next, you have to use “Tone, Semi-Tone” (known as a minor third).

Because of the mathematical nature of the Diminished chord, there are only three “clusters” of notes, which can then be rearranged like the Major and Minor Scales.

Cluster 1: C Eb F# A

Cluster 2: C# E G Bb

Cluster 3: D F Ab B

Use these clusters and rearrange them as you please. For example you could rearrange cluster 1 as Eb F# A C, etc.

Generally speaking, you can’t make a song based entirely on Diminished Chords, due to the fact that each cluster only has 4 notes. However, a Diminished Chord is perfect for adding a hint of darkness to your tune, and is brilliant when mixed with some Minor Scales.

Chords:

Chords are basically two or more notes played together. They are made up from a specific scale – for example the C major chord is made up of notes in the C major scale.

Usually, chords will include the first, third and fifth note of the scale, as well as possibly using other notes to give them colour. For example the basic chord of C major would be C, E, G. Then you could add the seventh note to it (in this case it is B). Really, it is up to the producer’s discretion how he/she goes about making a chord – just remember to stick to the scale you are using!

Chords will more than likely sound like shit if you play them on a complicated or layered synth patch. You want to be playing chords on sustained sounds such as strings or pads. Chords will really fill out your sound if used properly. You want your chords to be supporting the melody or bassline, and more than likely want to add some reverb so that it doesn’t sound too sharp. Make your chords blend in with the music and you’ll have mastered them!

Chord Inversions

Quite simply, chord inversions are when you rearrange the notes in a chord so that it sounds a bit different, and suits your arrangement better.

For example, if you were in the key of C major, you could have a drone of E playing underneath some strings playing the notes E G C E.

Due to the fact that the notes are the same, and have only been inverted, the chord will still be in key with the rest of the music. This is a great way to add a touch of variation to your music instead of using the same chord structure all the time.

Arpeggios:

Arpeggios are much easier to understand than they sound! They are quite simply the first, third and fifth note of the scale played as individual notes. For example the arpeggio of C minor would be C Eb G C etc.

A great example of an arpeggio is the bassline in Benga’s “Crunked Up”. He goes from playing the F# minor arpeggio backwards to playing the F minor arpeggio backwards. In other words, he is playing:

C# A F#, and then C Ab F

Experiment with a few Minor Arpeggios and a couple of Diminished Arpeggios, and you can’t go wrong in writing a huge bassline.

Suggested Reading

List of All Scales, With Finger Charts Included

Well that’s it folks. That’s basically all the music theory you need to know to start off with. As you grow more used to the various scales, you’ll notice that certain notes sound good with each other, whilst others don’t. I’m not here to tell you how to write music, I’m here to teach you the language of music. It’s up to you to write the poetry.

© Bruno Crosier (.klimaxx) 2008

Please let me know what you think of this guys!